Sending the right signals

Restoration of an early 19thC telegraph station on our island inspires me to flag up some thoughts about ancient signalling

Alderney, the island where I live and write, is not only rich in history from ancient times to late modern, it’s endowed with more knowledgeable historians per square mile than you might expect in any academic institution.

There are experts on archaeology, medievalists, Victorian age chroniclers (we have a lot of forts) and World War II factfinders for whom an island that contained the only Nazi concentration camps on British soil remains a seam of discovery (and horror) to this day.

Chief among these notables is Trevor Davenport, President of the Alderney Society which includes an amazing museum. So when I heard that Telegraph Tower was to be restored and placed alongside our Roman Fort and several impressive Victorian defensive strongholds as a tourist attraction, who else would I turn to for the rationale behind the idea.

This is what he told me.

Telegraph Tower is a prominent surviving landmark from the Napoleonic Wars in Alderney, standing near the south-west cliffs facing Guernsey. In August 1809, Sir John Doyle, who served as Lieutenant-Governor of Guernsey from 1803 until 1816 and worked tirelessly in improving defences during the Napoleonic Wars, approved recommendations for telegraphic communications between the Channel Islands.

During this tense period, armed naval cutters stationed in Alderney continued to provide the Admiralty with shipping intelligence, and it was proposed to erect a telegraph tower on Beacon Heights using Mulgrave’s semaphore system to communicate with the other Channel Islands.

Prior to and during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, there were numerous methods of signalling, and those used by the British army differed from those used by the navy. There were lights, flag systems, shutter systems and those using a combination of flags, balls and pennants.

(Bear with me dear reader because a little further on I shall reveal how the Pompeian army opposing Caesar got bored with shrill trumpet signalling and my hero in Libertas invented very early semaphore, among other tricks.)

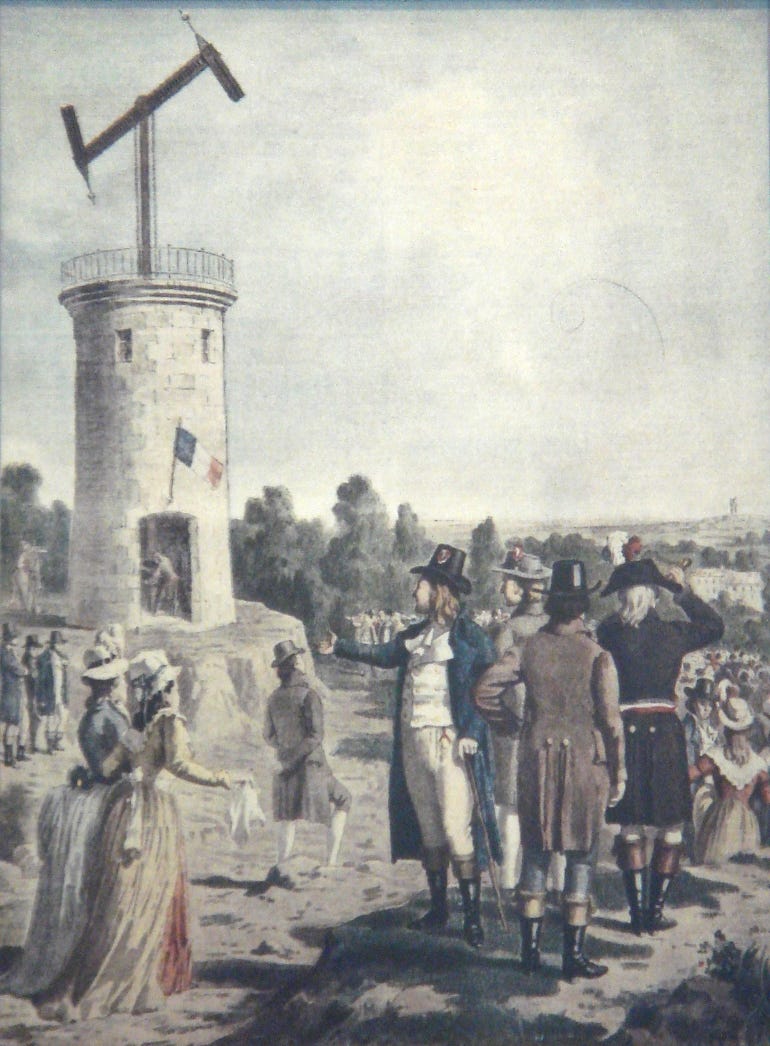

In France, a system of semaphore had been invented by Claude Chappe and his brothers in the late 18th Century. It used two arms on a connecting cross arm which could be pivoted to pass messages over long distances. Chappe’s system offered a potential 196-combination code and proved to be the world’s first effective system of telecommunications.

Peter Archer Mulgrave, described as ‘a commercial gentleman of ingenious mechanical ability’, is credited with the introduction of a similar but improved system into the Channel Islands between 1809 and 1810, but there are no illustrations from the time showing this type of semaphore in the Islands. Using semaphore, messages could be passed between stations in Guernsey, Sark and Alderney. The stations at Grosnez in Jersey, Jerbourg in Guernsey, Beacon Heights in Alderney, and Sark had their telegraph arms made extra-large to make them more identifiable across the sea.

Mulgrave's system made it possible for the first time to communicate distinctly and clearly over great distances. He was rewarded for his services by being appointed Channel Islands Inspector of Telegraphs.

Here’s a graphic supplied by Trevor Davenport of an earlier French system and alphabet samples. Frankly, G should have been F, but that’s the French for you…

Meanwhile, if you want to read more by Trevor (who has written many books and papers especially on Victorian and World War II activity in Alderney), here’s his tome on the Victorian Forts and Harbour – “a labour of love”.

So what of earlier signalling systems? As an author focusing largely on the Roman Republic (1stC BCE), here’s something I’d like to flag up (groan). Years ago, I had this idea that although the Roman army was astonishingly efficient and by-and-large swept all ‘barbarians’ aside with ease, they were commanded by grumpy, selfish and unimaginative old men. What if those they sought to conquer were actually more advanced in terms of inventiveness, humour and love of life, just a little less fortunate with their military systems?

Enter Melqart, a youth of Phoenician origin with an innate capacity to think outside the box. Just unlucky enough to live in the path of Caesar’s well-organised legions. In Libertas, he’ll go on to invent the hot shower, a primitive torpedo and the retracting centre-board. But as Caesar approaches from the north and pirates raid from the south, he develops a signalling system using what can only be described as very early Morse code.

And as Caesar brings his legions to oppose the sons of Pompey, Gnaeus and Sextus, at Munda (45 BCE), he is then called upon to use his skills to create a better system than blasting shrill notes on a trumpet to direct advance, retreat or repositioning.

So he invents semaphore on the spot using coloured flags and pre-arranged signals. He will stand on a hill near the battle lines and take direction from the Optimates’ second-in-command, Sextus Pompey. In this short excerpt, Melqart tests the commanders after explaining how his system works ahead of the battle.

I held up a black flag and pointed at Labienus.

‘Caesar,’ he grumbled reluctantly.

I moved it to the left.

‘Caesar engaging on the left.’

‘Whose left?’ Sextus interjected curtly, enjoying his seniority. ‘Yours or Caesar’s?’

Labienus scowled. ‘Obviously Caesar’s left because that’s the way the flag is pointing.’ He looked as if he would like to be fighting Sextus, not Caesar, but he controlled his petulance.

‘And if he raises it up and down?’ asked Sextus, sweetly.

‘Then it’s an attack at the centre, and if he waves it to the right it’s an attack in that direction…’

‘All right, all right,’ Sextus interrupted. ‘Let’s see if someone else is as clever as Labienus here. Dracus, what colour flag are you?’

‘Green,’ he replied triumphantly, ‘my favourite colour as it happens.’

‘So if you see a green flag moving to your right, what do you do?’ Sextus could be condescending without the offence being noticed by a warrior like Dracus.

With a sigh, Dracus said he would move the main force of his men to his right.

‘Excellent,’ declared Sextus. ‘Now who is represented by yellow?’

Labienus shifted in his seat and waved his fingers in an attempt not to look like a schoolboy.

‘Red?’

Gnaeus coughed, then said: ‘The least I expect is a cheer at my colour!’ At last, the mood was lightened and the officers crowding behind the generals gave a mock cheer.

Sextus held up his hands for quiet. ‘Now the complicated bit,’ he said, seriously. ‘Here’s Melqart with the colour combinations…’

And I explained to them how to recognise the different signals for weaknesses in the enemy ranks, where they were exposed, or the massing of troops for a concerted push.

Even, hopefully, if they were retreating…

Needless to say it all goes horribly wrong when Melqart’s arch-enemy discovers the signalling point and mucks everything up for the Optimates ‘rebels’. But that’s another story…

Books update

Catch up with my books and writings on my Linktree page. Here you’ll find more on the inventive Melqart in Libertas, nifty use of the Caesar Code in the Agents of Rome trilogy, and in Sea of Flames derring do by the crew of a Greek ship at the Battle of Actium. For something different, the story of David and Goliath as it might have been before the religious scribes got their hands on it – Line in the Sand.

Fascinating, Alistair! Thanks so much for this piece.