Today, I want to share some really interesting stuff (well I think so, hope you do too) that I found while reading Plutarch, author of prolific biographies, and other ancient historians. Such as a piratical Greek bent on revenge who chased down Mark Antony, a peculiar sacrificial rite, and an obscure attack by suckerfish on an ancient fleet.

The thing about history is that there’s always someone who knows more about it than you. This can be difficult if you’re trying to weave a gripping story around a well-documented period of history, but every so often you find a hidden gem.

I started research in earnest into the Battle of Actium (31 BCE) after completing a novella trilogy following the fortunes of a centurion recruited as a spy by Marcus Agrippa in the struggle against the Sicilian pirate, Sextus Pompey. Actium was an East v West sea-battle that altered the balance of world power. Sounds familiar?

I began my research with Lee Fratantuono’s excellent work The Battle of Actium (Pen & Sword), which I purloined from a friend who was enjoying a quiet read in a café-bistro near my home on the picturesque island of Alderney. The sort of place where you can always sniff sea air.

Then on to Plutarch (first century CE) and Dio Cassius (second century), both key historians for the facts, such as they are, although there are several others with interesting contributions including Appian of Alexandria and the geographer Strabo. The latter is a key character in the resulting novel, Sea of Flames.

Even Virgil’s Aeneid, published soon after that author’s death in 19 BCE, has thinly veiled references to Actium with images forged by the gods into the Shield of Aeneas: Augustus Caesar and Agrippa are favoured by the gods, Mark Antony and his Egyptian queen are not. Aeneas himself is symbolic of Augustus Caesar’s accomplishments in restoring order after years of civil war.

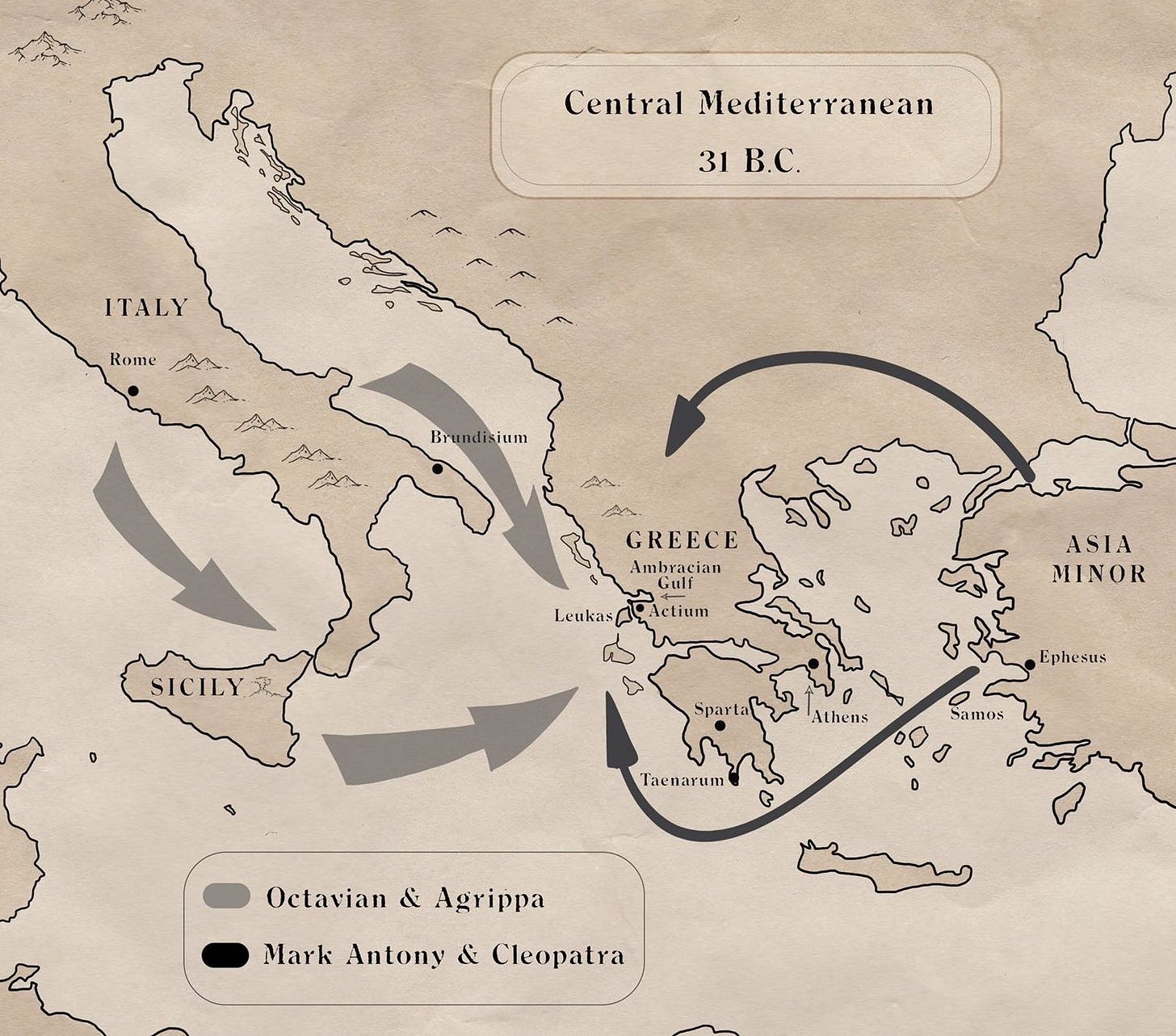

Here’s a map made by my wife Lynda showing the build-up to the pivotal battle:

Antony’s 500 ships (Plutarch) were cornered but he had 100,000 infantry and 12,000 cavalry, many provided by the array of foreign kings who came with him. Octavian was outnumbered both at sea (250 ships, albeit better equipped) and on land (80,000 infantry). What these days we would call a no-brainer.

Except for Antony and Cleopatra, it wasn’t. Plutarch’s view is that Cleopatra, holding her inebriated lover enthralled, persuaded Antony to fight at sea. Bigger ships, and twice as many as Rome had mustered. But when the navies clashed, Cleopatra fled with around 60 Egyptian ships.

Courage, revenge, defectors and spy-rings always make a good story. And there are plenty of gaps in the accounts of Plutarch and Dio to permit some tense plotlines.

And it was in Plutarch that I found Eurycles. A man so enraged over the murder of his father, Lachares, that he decked out his ship at his own expense and went to war against Mark Antony. Plutarch has Eurycles pursuing Antony after the general had fled on Cleopatra’s ship, announcing at the climax: “I am Eurycles the son of Lachares, whom the fortune of Caesar enables to avenge the death of his father.”

But (spoiler alert, but you knew this) he didn’t manage to kill Antony. There are messy suicides to follow the escapees’ flight back to Egypt and Burton & Taylor have a classic film to make. However, Plutarch reports Eurycles’ success against a certain other general’s ship, with no reference to the name of the commander in question, and there’s no mention of one Publicola after Actium. This senator was a nasty piece of work, easily worked into a story around Eurycles’ quest for revenge.

There’s the story, right there. Fill in the gaps. Create an almost piratical crew for Eurycles’ ship, add in some love interest, have the hero and his woman captured and tortured (by Publicola of course), escape against the odds and sail into the heat of a sea-battle.

Some of the interesting things I discovered included the local Actium custom of sacrifice by flinging victims off a cliff with birds attached to help them fly. As if. But it helped inform what Publicola might have done to Eurycles to win over the locals.

And what about the strange story of Mark Antony’s fleet being hindered when small sucker fish attached themselves to the keels of his ships? I’ve translated that as weed, worm infestation and unusual tidal flow.

Another subtle manipulation is Plutarch’s and Dio’s reports that Mark Antony burned around eighty of his (or Egypt’s) surplus ships before the battle. The scholar W.W. Tarn argued that this was actually Caesar Octavian’s doing. Did he send in fireships, an oft-repeated tactic since (e.g. Francis Drake v. The Spanish Armada 1588)?

I have spent many hours researching this story but I confess that, like a lawyer arguing a case in court, I have shone a light brightest on the parts that help my tale of Eurycles and his plucky ship’s crew.

Sea of Flames was published in July 2022 by Sharpe Books.

A fuller version of this article appears in Issue 12 of Inside History magazine, on sale now:

Loving Lynda’s map! Great piece, Alistair.